serás más macho: Abel Guzmán

serás más macho

Abel Guzmán

September 16 - October 21, 2023

Press Release

la Beast gallery launches into fall with a presentation of new works by Abel Guzmán. The exhibition, titled serás más macho, marks the artist’s first solo effort with the gallery and celebrates his Los Angeles debut. A painter by training, Guzmán turns to drawing and sculpture, the latter an exploration of traditional water vessels, to convey the urgent intersectional politics that fuel his practice and give immediate, physical form to those concerns. Issues of gender and its influence on social constructions of family, identity, and sexuality come to the fore in Guzmán’s pointed critique of the machismo culture in which he was raised.

The phrase “serás más macho” rejects perceived effeminacy (i.e., weakness) while daring the individual to substantiate his grit through demonstrations of “manliness” that satisfy the call for arrogance, vulgarity, or an indifference to brutality. It is a command that insinuates doubt in a manner more complex and aggressive than its direct English translation of “you will be more macho.” Guzmán uses the phrase to scrutinize sexist, queer-phobic, and masculine value systems.

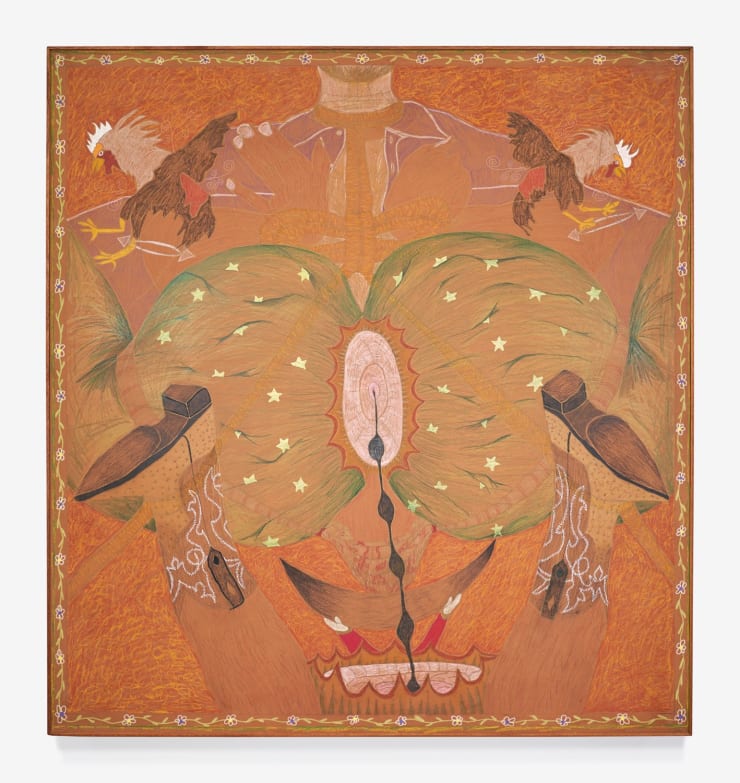

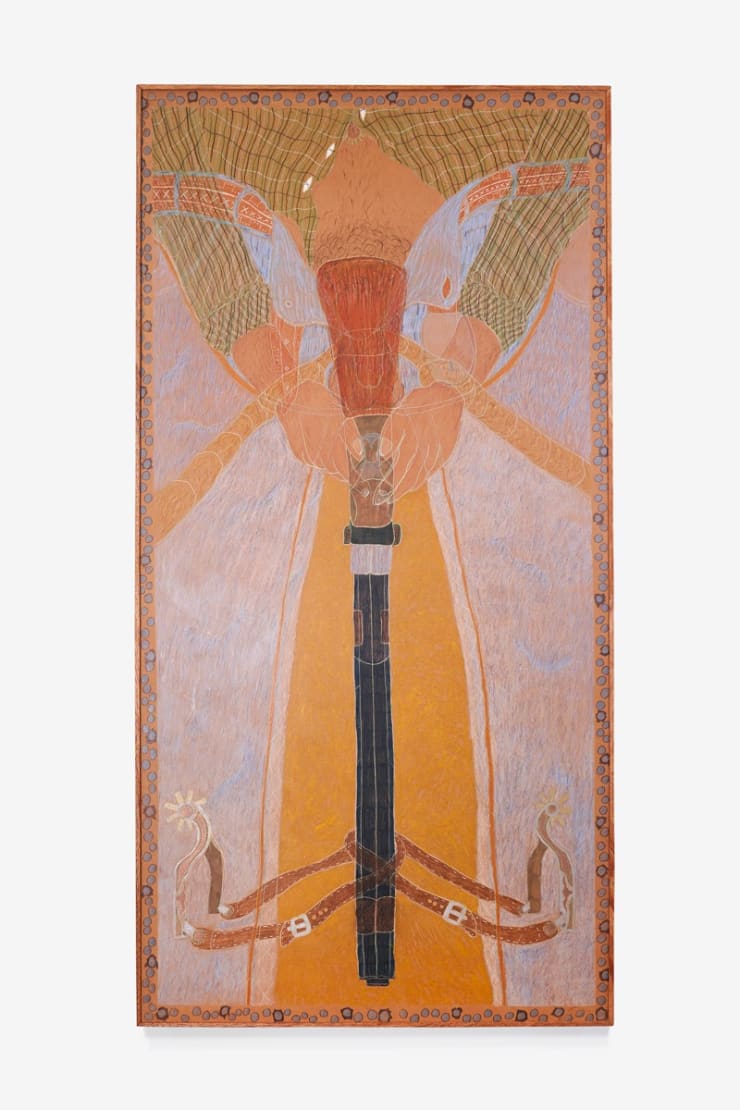

In the context of his Mexican-American upbringing, nowhere does Guzmán find greater fodder for this take down than in the ideologically saturated iconography of the Catholic church (brought to Mexico during Spanish conquest). The appearance of icons such as the sickle moon and the mantel embedded with stars, frequently tied to the Virgen de Guadalupe, are laden with symbolic reference as they are with autobiographical trace. Their reconstitution as transcendental fetish gear in the drawing con tu bendición (With Your Blessing), activates a blasphemous disavowal of Catholic authority. Likewise, the trappings of vaquero fashion that give shape to the drawing’s predominant gay figure, performs a double function by alluding to a damning example of hetero-patriarchy while simultaneously appropriating this archetype for subversive queer enjoyment.

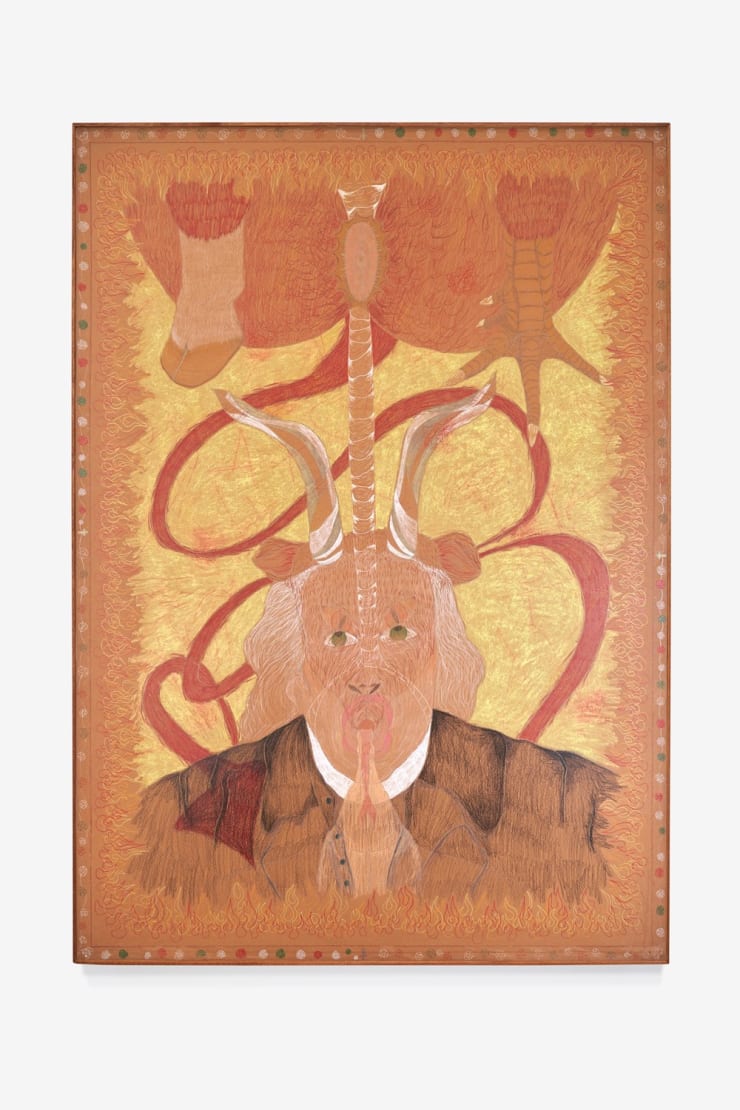

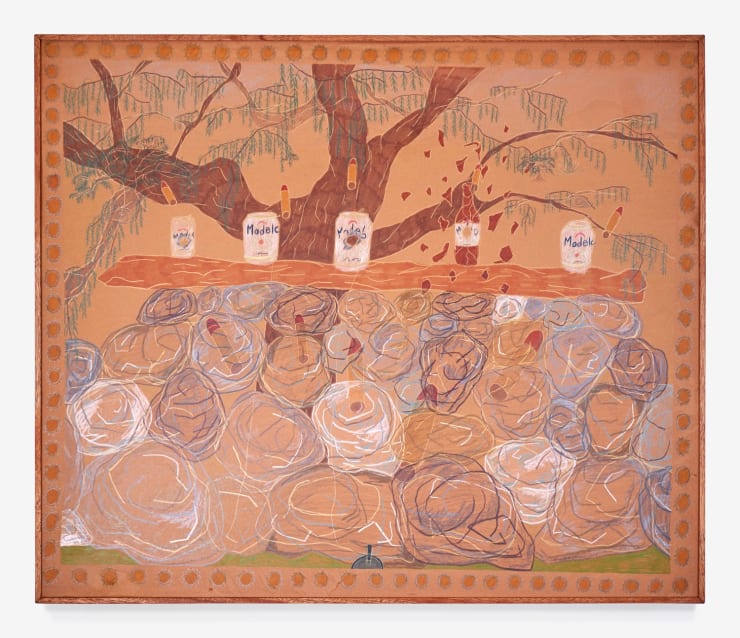

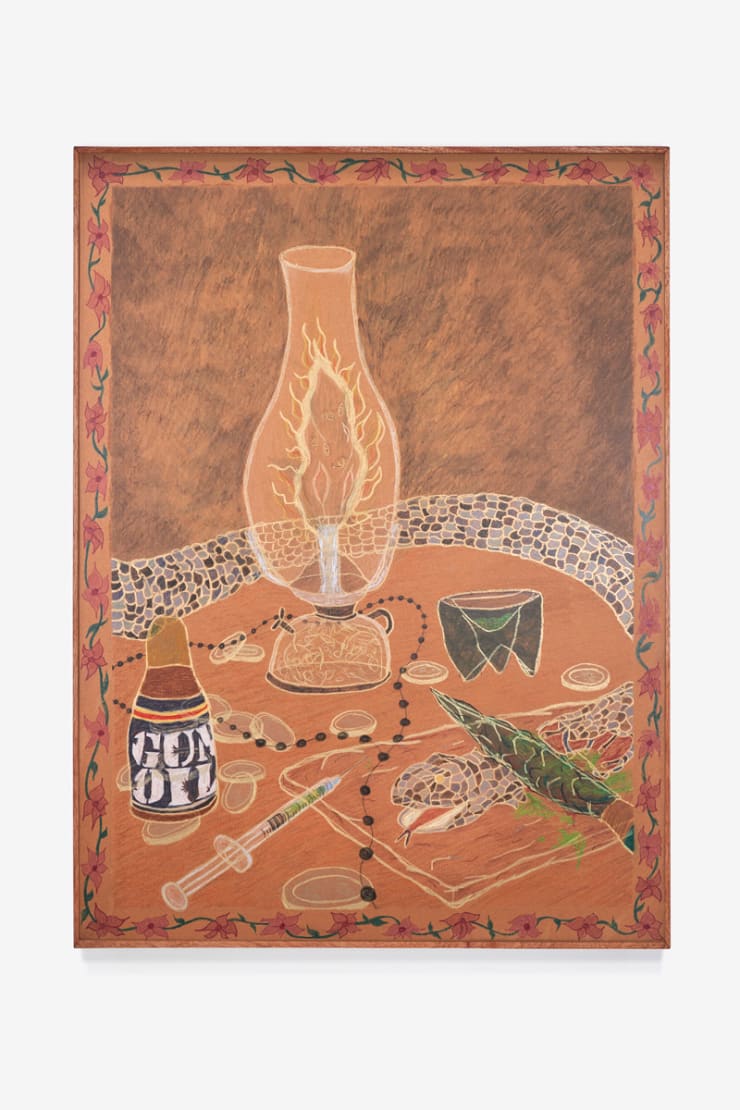

Guzmán ups the ante of his protest against the conventions of organized religion with ¡chinga tu padre! (Fuck Your Father!), a portrait of a Catholic priest fornicating with the devil. A comment on the hypocrisy of the church in light of its many scandals, and an allegory of hypocrisy itself, it raises the question of what it means to revel in the forbidden, and it ultimately asks what forces sanction delight and dictate taboo. A quieter exploration of this sentiment is found in el placer de comer la fruta prohibida (The Pleasure of Eating Forbidden Fruit). At first blush, a traditional still life image. The impetus for its making was to wrest the apple from Eden’s misogynistic legacy and frame it as a sign of the pursuit of pleasure. A jockstrap and a tub of Albolene hint at lusty exertions just out of sight, a sexcapade where the apples provide welcome sustenance.

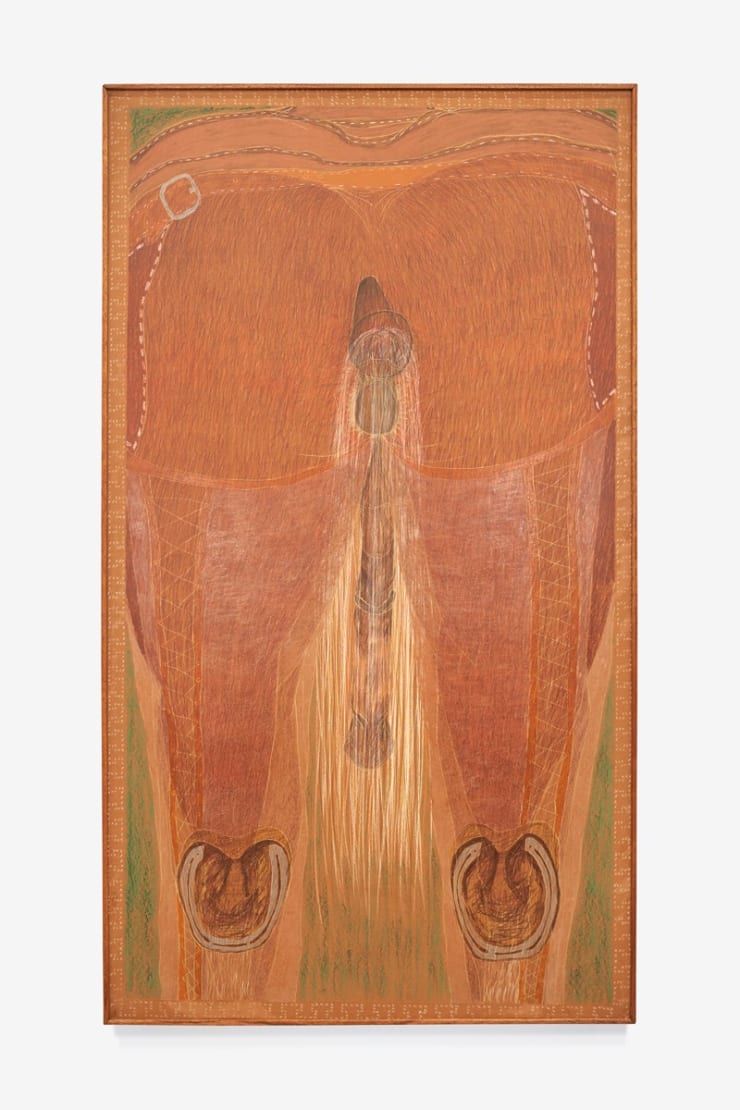

The namesake work, serás más macho, bares a rear view of the kneeling male figure. A horse-tail butt plug occupies the drawing’s focal point, working in tandem with the figure’s hoofed feet to depict a character whose mythic proportions are verified by his pendulous endowment. A different facet to this interpretation relies on another shade of meaning carried in the exhibition’s title, that being “macho” in Spanish, also defined as male mule, characterizes a creature unto itself. The figure’s large penis states the obvious. Masculinity, like the vanity of the baloney pony, drives some men to define their existence through the instrument between their legs.

The testicle-forward huevón (Big Balls or Lazy) addresses this very scenario and originates from Guzmán’s research into chemical body sculpting as a pathway to idealized masculine physiques. Note that huevón, like all the drawings in the show, is rendered on brown paper, chosen to shift the base of his imagery away from the default white sheet. It also picks up his fascination with Catholic imagery. Here, as elsewhere, the anus is shown circled by a heavenly mandorla. The divine figure is profaned, yet its absence comes not (only) from a place of sacrilege but the artist’s sense of mysticism as passed to him through a familial line of matriarchal brujeria. Guzmán embraces the celestial void and summons the ecstasy of outré pleasures that emanate beyond the confines of the physical self.

And just as he considers the body a receptacle for these metaphysical experiences, he considers the crystalline sculptures that he builds from pipe cleaners and saline solutions, to be vessels for the energies coursing through his works on paper. Grotesque, corporeal, sullied, and maimed, these objects speak to the violence enacted upon the bodies of women and queer people of color, so many of whom have been oppressed by patriarchal and colonial fallout. The magic in Guzmán’s practice works against these oppressive forces with willful flagrance, combining pleasure with protest and a dare to challenge his encouragement of either.

-

Abel Guzmán, ofrenda al sol, 2023

Abel Guzmán, ofrenda al sol, 2023 -

Abel Guzmán, ofrenda a la luna, 2023

Abel Guzmán, ofrenda a la luna, 2023 -

Abel Guzmán, ¡chinga tu padre!, 2022

Abel Guzmán, ¡chinga tu padre!, 2022 -

Abel Guzmán, Energy Vessel (No.16), 2023

Abel Guzmán, Energy Vessel (No.16), 2023 -

Abel Guzmán, apunta y dispara, 2023

Abel Guzmán, apunta y dispara, 2023 -

Abel Guzmán, Energy Vessel (No.22), 2023

Abel Guzmán, Energy Vessel (No.22), 2023 -

Abel Guzmán, con tu bendición, 2022

Abel Guzmán, con tu bendición, 2022 -

Abel Guzmán, Energy Vessel (No.20), 2023

Abel Guzmán, Energy Vessel (No.20), 2023 -

Abel Guzmán, armado y cargado, 2023

Abel Guzmán, armado y cargado, 2023 -

Abel Guzmán, el placer de comer la fruta prohibida, 2022

Abel Guzmán, el placer de comer la fruta prohibida, 2022 -

Abel Guzmán, Energy Vessel (No.19), 2023

Abel Guzmán, Energy Vessel (No.19), 2023 -

Abel Guzmán, serás más macho, 2022

Abel Guzmán, serás más macho, 2022 -

Abel Guzmán, Energy Vessel (No.21), 2023

Abel Guzmán, Energy Vessel (No.21), 2023 -

Abel Guzmán, una charreada de coleadores, 2023

Abel Guzmán, una charreada de coleadores, 2023 -

Abel Guzmán, Energy Vessel (No.25), 2023

Abel Guzmán, Energy Vessel (No.25), 2023 -

Abel Guzmán, huevón, 2023

Abel Guzmán, huevón, 2023 -

Abel Guzmán, Energy Vessel (No.23), 2023

Abel Guzmán, Energy Vessel (No.23), 2023 -

Abel Guzmán, la luz y el veneno, 2023

Abel Guzmán, la luz y el veneno, 2023 -

Abel Guzmán, Energy Vessel (No.24), 2023

Abel Guzmán, Energy Vessel (No.24), 2023 -

Abel Guzmán, macho macho man , 2023

Abel Guzmán, macho macho man , 2023 -

Abel Guzmán, no se dio cuenta de su propio mal presagio, 2022

Abel Guzmán, no se dio cuenta de su propio mal presagio, 2022 -

Abel Guzmán, Energy Vessel (No.26), 2023

Abel Guzmán, Energy Vessel (No.26), 2023